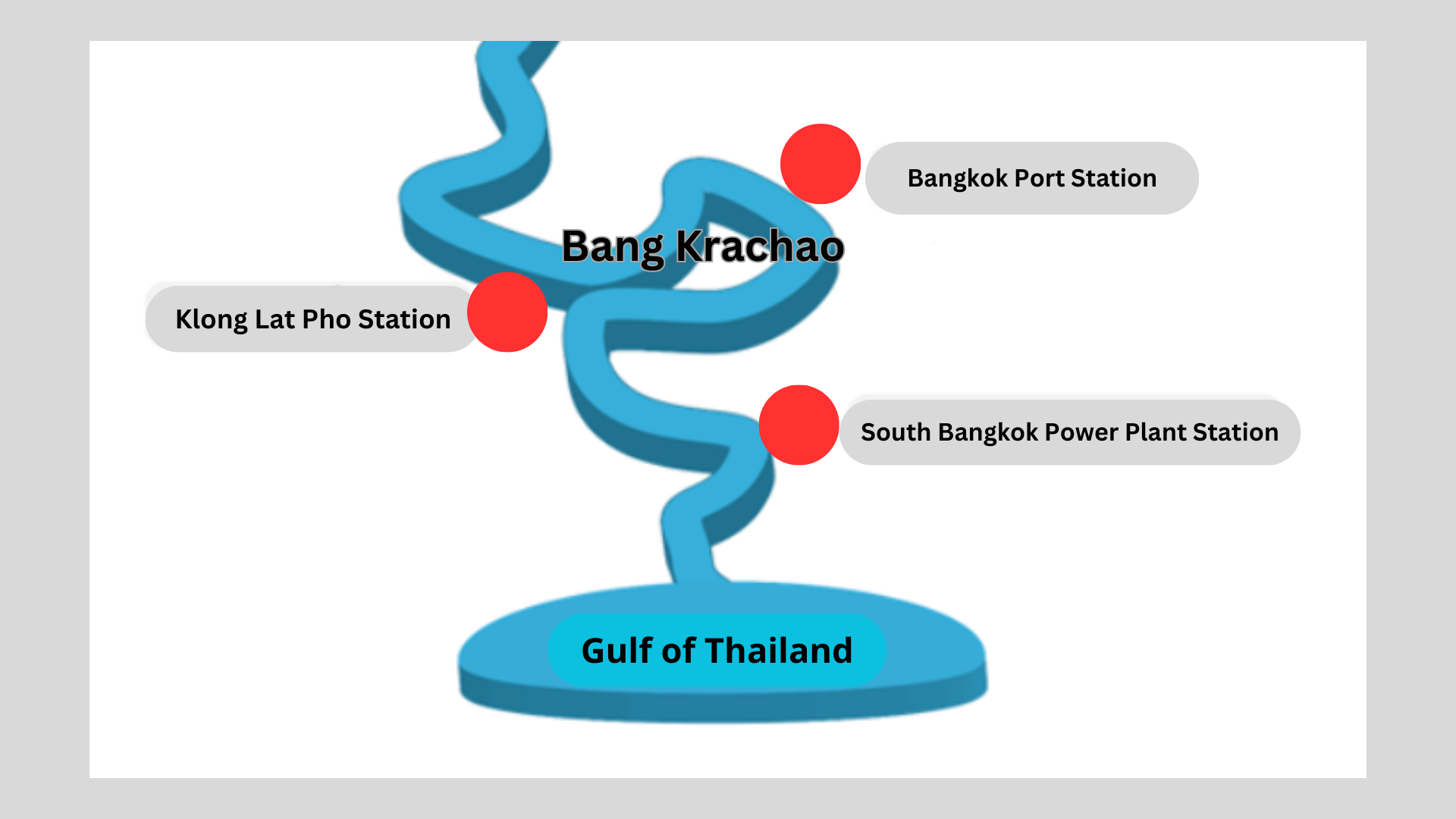

Bang Krachao, often called the green lung of Bangkok, is a rare patch of nature in the heart of one of Southeast Asia’s busiest cities. Surrounded by the bend of the Chao Phraya River, it has managed to resist large-scale development and preserve its lush greenery. But beneath its peaceful appearance, the area faces a serious environmental challenge: poor water quality caused by saline water inflow. This problem threatens not only the ecosystem but also the livelihoods of locals who rely on agriculture and green tourism.

In response, a group of CMKL students has stepped in with a project that combines community insight, machine learning, and mobile technology. The team built a salinity prediction model using data from nearby monitoring stations and integrated it with a simple mobile app that helps gate operators make better decisions. By predicting when salinity will spike, the system allows for proactive control of water gates. This, in turn, helps prevent damage to crops and plants and encourages residents to make use of their land again.

Before this project, water gate management in Bang Krachao was fully manual. Locals had to report signs of poor water quality, and operators had to travel to each of the 28 gates to open or close them. Sometimes, by the time they reacted, it was already too late. With the new model, operators can monitor predicted water conditions in advance and take action earlier.

In an interview, the research team shared that the local community was very receptive to the project. “They were just happy that someone cared. For years, they had to handle things on their own, so when we showed up with a tool that could help, they welcomed the idea with open arms,” one of the team members said. Residents were particularly interested in the use of Wi-Fi and mobile apps to control the gates remotely. Unknown to many in the community, another university had previously installed a basic remote control system. However, it was unclear if that system used any predictive modeling or advanced data analysis. That is where this new AI-powered project stands out.

When asked about possible roadblocks, the team said there were no major legal or regulatory issues. The only concern is the cost of maintaining the system in the long term. Currently, the project has not received any external funding, but local stakeholders expressed interest in helping secure support if the system proves effective.

The research team began by defining the problem through conversations with local experts. They then gathered and cleaned years of salinity data, trained a machine learning model using LSTM architecture, and designed a user interface using Figma. The model performed well for salinity values below 25 and showed consistent predictions across several monitoring stations. While there is still room for improvement, especially in reducing bias, the results are promising.

Looking ahead, the team plans to refine the model further, improve the app design, and possibly automate the gate control system fully. The lessons learned have reinforced the importance of communication and adaptability. With continued effort, this project could be a major step in preserving Bang Krachao’s environment and revitalizing its green economy.